The Top 5 things I didn’t get to in 2013

New Year’s is a time for reflection and aspiration, but these are fueled by fruitful regret! Over the next week or so (okay, by now it’s been more like months), we’ll be looking back longingly at art, comics, books and music I should have paid more public attention to in the 12 months just past — and pledging to make all our cultural appreciation immediate and immortal!

Chain of Fools: Silent Comedy and Its Legacies from Nickelodeons to YouTube by Trav S.D.

BearManor Media

Early in this family history of physical comedy, humorist, performer and variety-entertainment impresario Trav S.D. recalls how books alone brought to life a lost world of silent-movie comedy for him as a youth in the 1980s, noting the obstacles inherent in this activity as being like imagining the taste of gourmet dishes solely from food reviews. But Trav himself lays out a banquet of reminiscence, demonstrating how much of entertainment and edification occurs in the imagination, which is his most essential and assured medium. Like Wynton Marsalis, who was unjustly criticized in some quarters for acting, as frequent narrator of Ken Burns’ Jazz series, disingenuously “as if he had been there,” Trav wipes that concern away by making me feel like I was there. Also early in the book he proposes that Charles Chaplin held onto silent moviemaking so much longer than any of his contemporaries because he realized that the basics of storytelling do not require sound; Trav has a sense of the primal connections we make among events and with a work of art. That’s why his lively prose, itself dependent on words, paints pictures and conjures pratfalls — and historical turning points — that don’t just lead us to the source material but open a wide, clear window on it.

It’s a common stumble of arts criticism itself that the act of analysis makes authors feel constrained to convey a seriousness in their phrasing that disserves the pleasurable values of what they’re describing to begin with — for pop to be honored, it doesn’t have to become respectable, and shouldn’t be. Trav’s prose is as energized and witty and open to the unpredictable and unforeseen as the high and low masterworks he considers; like all the best criticism it can’t compete with its subject but does complement it.

Trav’s cultural archeology is flawless, like he’s listening for the echoes of ancient laughter and feeding it new lines. He starts by explaining that some of the earliest clowns (performers preceding written-down theatre) were the mimes of ancient Greece (“mime” in this case for “mimesis” or imitation, placing them among the first memes); interestingly, this profession was so disreputable that it was strictly kept separate from the rites for the drunken god Dionysus, though it is hard to say now who has had the more enduring and fruitful Hangover.

Trav continues on through the Medieval-and-later European tradition of traveling pantomime and other entertainment, likening its temporary open-air stages to “the back of a pick-up truck” in the first of a book-full of phrasings in which he invokes historic practices by renewing them in the context of contemporary understanding. The conceptual continuum of Trav’s thinking is dazzling, as when he takes us through the centuries of suppression of European entertainment by the church, and the implicit origins of short-subject film comedy in brief scenarios played around or between more legitimate long-form culture (operas, ballets), as well as the disrepute that performers sustained across all these centuries, blowing through their material and your town fast. Life is short and feels long, so the jokes have to be even quicker.

Like a master career comedian (which he is), Trav retells stories that are old to him in ways that make them brand new, with both period patois and fresh turns of phrase. As important as it is to convey a thrice-told tale with its punchline intact, Trav also delves into not just the comic but the serious business of interpretations that have not been extracted before. His identification of early silent-comedy farce as a kind of proto-countercultural modeling of an anarchic spirit, and his perception of the greater role of blockbuster-scale disaster played for laughs (falling buildings, big explosions) as a diminishing of the individual’s scale by the very technology that’s also making these SFX advances possible, are all about what story is being told unconsciously by the jokes we tell on the surface.

Like a master career comedian (which he is), Trav retells stories that are old to him in ways that make them brand new, with both period patois and fresh turns of phrase. As important as it is to convey a thrice-told tale with its punchline intact, Trav also delves into not just the comic but the serious business of interpretations that have not been extracted before. His identification of early silent-comedy farce as a kind of proto-countercultural modeling of an anarchic spirit, and his perception of the greater role of blockbuster-scale disaster played for laughs (falling buildings, big explosions) as a diminishing of the individual’s scale by the very technology that’s also making these SFX advances possible, are all about what story is being told unconsciously by the jokes we tell on the surface.

Trav has a gift for cross-referential metaphor, as when he describes Chaplin’s improvisation of his films as being like using “the whole apparatus of the film studio [as] his pipe organ to compose on”; this talent serves Trav well in divining the symbolism that connected certain performers to the strivings of their viewers, forming more than just a bond of stage-and-audience call-and-response, as with Chaplin the recent immigrant embodying America’s possibilities for self-re-creation and Harold Lloyd (whose hilarity ensued while he was trying to play by the rules rather than flout them like Chaplin’s character) embodying the consolidation of comfort and following of social standards felt necessary by more long-established Americans.

To make these links Trav carries an encyclopedic, yet discerning, knowledge of every era’s context, sketching what was going on around a given comedian’s defining traits (like the acrobatic Douglas Fairbanks — known as a comic actor long before he was an early action hero — being surrounded by the first superstar body-builders, the popularization of vigorous outdoor activity by iconic president Teddy Roosevelt, etc.).

To make these links Trav carries an encyclopedic, yet discerning, knowledge of every era’s context, sketching what was going on around a given comedian’s defining traits (like the acrobatic Douglas Fairbanks — known as a comic actor long before he was an early action hero — being surrounded by the first superstar body-builders, the popularization of vigorous outdoor activity by iconic president Teddy Roosevelt, etc.).

Trav’s populist scholarship acknowledges the need to connect with listeners in the way that all successful theatrics and effective educational transmission require, as when his historical lens takes in both the true phenomenon of a suis-generis genius like Buster Keaton, whose instincts and inventiveness were innate, and the context in which this supposedly (and avowedly) untutored humorist had to be influenced by cultural advances in ideas that (as often happens) we view as rare and recent but in fact were enjoying a first surge of discovery at an earlier time before the lid came down again (in Keaton’s case, the models of surrealism to be found mass-market in L. Frank Baum stories, Winsor McCay cartoons, and outlandish amusement park design as well as art galleries and literary journals). “No one comes from nowhere,” Trav remarks; we are always learning, even and maybe especially when we are being entertained.

The book brings to life personalities that even in their day were known to us mostly as their press-managed projected shadows, but reading those outlines Trav comes up with inspired psychological profiles (as with the fatalism of Keaton’s Midwestern, abused-child-star upbringing translating into an existential stoicism in his roiling comedy and impassive persona).

In the same way that modern vernacular and references refresh and clarify his content, Trav remains adaptable to where the results of individual artists’ experiments lead; for instance, affirming that some kind of emotional relation is needed to follow a comedic character through a whole feature rather that the shorts that once dominated Hollywood, while also acknowledging that, for the right type of completely absurd personality (Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers), conventional story can be a constraint which ruins the new territory that visionary jesters can take themselves and us to. Form-follows-function can also point the way to shapeless silliness when that’s what does the job (and when it is in fact just defining a new geometry we had to traverse the whole contours of to see).

However, Trav has a connoisseur’s eye for what should be left out of the frame. He persuasively argues that the prevalence of radio as the precursor to TV refocused film audiences to the verbal from the physical in a way that impaired comedy when films went from silent to “talkie,” a case of technological advances actually representing a narrowing of options in the way we can fixate on them at first.

The book is a continual valued tutorial; I hadn’t known that pioneering comedy mogul Mack Sennet is partially responsible for the Miss America Pageant as well, or that Jacksonville, Florida was once a movie-making mecca. And throughout you get an idea of the kind of master-class Trav could run on how to get to the heart of what’s funny by acquainting yourself with that heart of your own (while also training your mind to understand what subjects stick with the audience as an odyssey into how they make sense of the world, and not just a diversion from it they’ll quickly forget). “The bird doesn’t know it’s singing,” he says, “it just does it” — artistry is intuitive, and can be an intention of the soul even if the artist is unaware and the consciousness of this only comes in those who are there to hear the song.

The book is a continual valued tutorial; I hadn’t known that pioneering comedy mogul Mack Sennet is partially responsible for the Miss America Pageant as well, or that Jacksonville, Florida was once a movie-making mecca. And throughout you get an idea of the kind of master-class Trav could run on how to get to the heart of what’s funny by acquainting yourself with that heart of your own (while also training your mind to understand what subjects stick with the audience as an odyssey into how they make sense of the world, and not just a diversion from it they’ll quickly forget). “The bird doesn’t know it’s singing,” he says, “it just does it” — artistry is intuitive, and can be an intention of the soul even if the artist is unaware and the consciousness of this only comes in those who are there to hear the song.

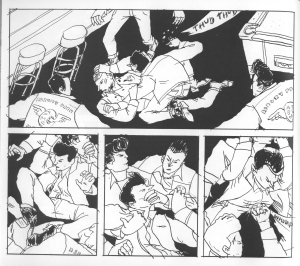

The book’s handful of flaws warrant much fewer than a thousand words: The scarcity of pictures is something you miss once you have read these stories, though you don’t find yourself wishing for them while making your way through Trav’s illuminating prose. In a discussion of the limited opportunities for African-American actors in the silent era, a footnote mentions Charles Lane’s much-later cult favorite Sidewalk Stories from 1988 and then never brings it up again, a bit maddeningly. And an over-apology for Chaplin’s (silly, irresponsible) celeb-statesman defense of the Soviet Union, in the face of the tyrannical McCarthyism that got him kicked out of the U.S. for it and is deemphasized by Trav, seems the one time when his grasp of historical context and proportion eludes him.

He can be allowed to miss one or two things since he is typically projecting magic moments and whole centuries of movement we otherwise couldn’t witness, or showing 20-20 vision for things no one saw at the time. His paralleling of the gruesome proto-torture-porn of the Three Stooges to the golden era of monster movies happening at the same time (the classic Frankenstein, Dracula and other franchises) is inspired, and causes a compact comic masterpiece in a brisk paragraph pointing up Larry, Moe, Curly and Shemp’s comparisons to slasher-movie/house-of-horrors psychos (fixating, or instance, on their neglectful, chopped or absent hair styles, which he likens to demented mad subgeniuses, head-hacking serial killers and patients shaved for brain surgery. Now that’s funny!)

Trav needs to be as good an anthropologist as archaeologist in later chapters; silence can be right in the midst of modern commotion, but we don’t always stop to consider it that way. Harpo Marx was of course a lonely last-man-standing for pantomime in the center of hyper-verbal farces. Otherwise, Trav looks for flare-ups of the physical in our joke-obsessed current comedy canon.

Trav needs to be as good an anthropologist as archaeologist in later chapters; silence can be right in the midst of modern commotion, but we don’t always stop to consider it that way. Harpo Marx was of course a lonely last-man-standing for pantomime in the center of hyper-verbal farces. Otherwise, Trav looks for flare-ups of the physical in our joke-obsessed current comedy canon.

Slapstick itself relies on the eyes, and the kinesthetic sense, and space, not words or explanations, though it does tell a story, like the dance that probably preceded spoken language among our ancient forebears. In this understanding Trav both tracks the persistence of precision slapstick — which mostly emigrated to TV after the 1940s, through veteran clowns like Red Skelton — and defines the debased variety (mere mayhem at the hands, feet and power-tools of the Stooges; mugging and contortions unconnected to the advancement of any story or delineation of any character by Jerry Lewis). He brings up the resurgence of formal clowning schools and popularity of theatrical clowning festivals throughout the 21st century world, and notes Sacha Baron Cohen as a standard-bearer (trained in this discipline and certainly a full-body comic in addition to his modern vaudevillian multicultural shtick).

Jim Carrey is conspicuous by his absence, perhaps lying unnoticed somewhere at the bottom of the Jerry Lewis file-folder, though I’d be interested to know what Trav makes of Carrey’s commute between pure farce and his Chaplinesque attempts (and occasional success) at art-house gravitas (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind) and Keatonesque darkness (The Cable Guy, I Love You Philip Morris). Trav does identify present-day makers of entirely silent movie comedies, and the success of his way of thinking is to get me noticing examples he doesn’t mention of surviving strains of visual comedy in venues where it feels so natural that I at first don’t realize that a revolution is being reborn — Leonardo DiCaprio and Jonah Hill’s drug-stupored flounderings in The Wolf of Wall Street; Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer’s Sisyphus-like struggles with fire-escape ladders and too-narrow doorways on Broad City; the improvised soundless side-stage café/cocktail-party business by the ensemble, especially dance-trained Stephanie Willing, in Ian W. Hill and Berit Johnson’s play The Strategist.

In short, and long, the show goes on, and while I didn’t want this book to end, Trav demonstrates that there is in truth no final act. Talk is cheap and laughs are gold, and in Chain of Fools Trav S.D. retells a grand story and epic punchline in your head, with a full and shining silence.

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4